Here We Come A-Wassailing: A Toast, a Tradition, and a Winter Drink With Deep Roots.

A few weeks ago, my youngest son and I were talking about Christmas and all the things we’re planning to do this year—one of which is his annual batch of homemade eggnog. He informed me that this year he’s also going to make wassail, a drink I had never heard of, much less tasted. I asked, “What is wassail, and what inspired you to make it?” He admitted he wasn’t entirely sure what it was, nor had he ever tasted it, and then added, “I just like how the word sounds—wassail.”

And so, my research began.

Wassail. Even before I knew its history, the word itself sounded like something rescued from the footnotes of a Dickens novel—cheerful, slightly archaic, and definitely belonging to winter. The more I looked into it, the more I realized that my first impression was exactly right. Wassail is older than the modern Christmas tree, older than the idea of Santa Claus, older even than many of the holiday traditions we think of as ancient. It has traveled through centuries carrying with it little wisps of language, folklore, and ritual—tiny breadcrumbs of the world that came before ours.

At its earliest roots, wassail wasn’t a drink at all. It was a greeting: the Old English wes hál, meaning “be well” or “be in good health.” In an age when winter was more than a decorative season—when cold months were lean and long and sometimes dangerous—this blessing mattered. To say wes hál was to wish someone wellness in the deepest sense: health of body, hearth, and home. Over time, this spoken blessing fused with the communal rituals of winter feasts, where a shared bowl of warm spiced ale or cider made the rounds of the great hall. Whatever was in the bowl, the sentiment remained the same. You raised it to your neighbor and wished them well.

At its earliest roots, wassail wasn’t a drink at all. It was a greeting: the Old English wes hál, meaning “be well” or “be in good health.” In an age when winter was more than a decorative season—when cold months were lean and long and sometimes dangerous—this blessing mattered. To say wes hál was to wish someone wellness in the deepest sense: health of body, hearth, and home. Over time, this spoken blessing fused with the communal rituals of winter feasts, where a shared bowl of warm spiced ale or cider made the rounds of the great hall. Whatever was in the bowl, the sentiment remained the same. You raised it to your neighbor and wished them well.

By the Middle Ages, that simple phrase had settled into the form we know now: wassail. And with the new word came new customs—drinking traditions, to be sure, but also the beginnings of the winter celebrations that would one day blossom into our modern Christmas season.

In its earliest centuries, wassail was most closely associated with Twelfth Night, the grand finale of the Twelve Days of Christmas. Today we might mark the end of the holidays by taking down the tree or resolving to eat fewer cookies. In centuries past, Twelfth Night was an event of considerable merriment—plays, feasts, songs, masks, and always the shared bowl of wassail. The drink wasn’t merely refreshment; it was a symbol of the season itself, a warm punctuation mark at the end of Christmastide.

In its earliest centuries, wassail was most closely associated with Twelfth Night, the grand finale of the Twelve Days of Christmas. Today we might mark the end of the holidays by taking down the tree or resolving to eat fewer cookies. In centuries past, Twelfth Night was an event of considerable merriment—plays, feasts, songs, masks, and always the shared bowl of wassail. The drink wasn’t merely refreshment; it was a symbol of the season itself, a warm punctuation mark at the end of Christmastide.

Wassailing traditions tended to branch in two directions. The first was what we would now call caroling, though the original form was less tidy and more spirited than the polite doorbell-choirs we imagine. Groups of wassailers went house to house, singing in exchange for food, drink, or a generous splash ladled right from the family’s wassail bowl. Their songs often walked a fine line between blessing and bargaining:

“We are not daily beggars

That beg from door to door,

But we are neighbors’ children

Whom you have seen before.”

It’s a reminder that hospitality once came with a bit of good-natured haggling—something modern hosts might find refreshingly honest, if slightly chaotic.

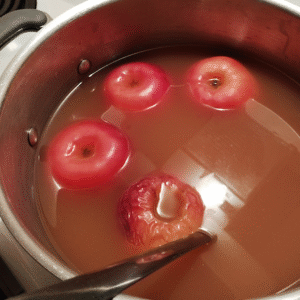

The second branch, orchard wassailing, is the piece of the tradition that feels most like stepping into a living postcard from long ago. In cider-making regions of England, Twelfth Night meant bundling up, gathering lanterns and torches, and heading to the orchard to bless the apple trees for a fruitful year ahead. Villagers sang to the trees, rattled pots and pans to chase off whatever winter spirits might dampen next year’s harvest, poured a little warm drink onto the roots as a libation, and crowned the event by placing a piece of cider-soaked toast in the branches for the “good” spirits. From this practice—so historians suggest—comes our modern term toast in celebration.

The second branch, orchard wassailing, is the piece of the tradition that feels most like stepping into a living postcard from long ago. In cider-making regions of England, Twelfth Night meant bundling up, gathering lanterns and torches, and heading to the orchard to bless the apple trees for a fruitful year ahead. Villagers sang to the trees, rattled pots and pans to chase off whatever winter spirits might dampen next year’s harvest, poured a little warm drink onto the roots as a libation, and crowned the event by placing a piece of cider-soaked toast in the branches for the “good” spirits. From this practice—so historians suggest—comes our modern term toast in celebration.

What captures my imagination most is the element of hope in these customs. Standing in the cold, the orchard bare and quiet, people still believed their humble ceremony mattered—that sound, warmth, and community could stir new life. Whether or not it actually awakened the trees, it awakened something else: a sense of togetherness carried forward in the middle of winter.

When wassail finally crossed the Atlantic, carried over by English settlers, it came without much of the ritual fanfare. America has always had a way of simplifying old traditions, sanding them down to their essential comforts. What remained was the drink—warm, spiced, communal—but it shifted from an outdoor celebration to a kitchen-table one. By the early nineteenth century, American cookbooks recorded versions that leaned heavily on cider, sometimes apples roasted and dropped into the bowl, sometimes ale or wine if the household kept it, sometimes citrus as those fruits became more widely available via railroads and coastal trade.

When wassail finally crossed the Atlantic, carried over by English settlers, it came without much of the ritual fanfare. America has always had a way of simplifying old traditions, sanding them down to their essential comforts. What remained was the drink—warm, spiced, communal—but it shifted from an outdoor celebration to a kitchen-table one. By the early nineteenth century, American cookbooks recorded versions that leaned heavily on cider, sometimes apples roasted and dropped into the bowl, sometimes ale or wine if the household kept it, sometimes citrus as those fruits became more widely available via railroads and coastal trade.

By the 1950s, wassail had settled into the landscape of holiday entertaining. Vintage magazines of the era loved it—those cozy, mid-century pages filled with smiling families in matching sweaters, a punch bowl glowing like sunset on the sideboard. This was the era when American wassail began to taste the way we recognize it now: cider brightened with orange and lemon, warm with cinnamon and cloves, and often simmered with a tea bag or two—a little trick housewives used when alcohol wasn’t part of the menu. The drink became less ceremonial and more welcoming, the kind of thing you made when neighbors dropped by with a tin of fudge or the youth choir showed up at your front door unexpectedly.

What struck me most while researching all this is how few drinks carry such a long cultural through-line. Wassail is a small example of something larger: the way food and drink serve as vessels for history. While the orchard rituals and medieval halls have slipped into legend, the heart of the tradition remains the same. Wassail has always been about community, about wishing one another well, about finding warmth together in the coldest, darkest stretch of the year.

And though I didn’t grow up with wassail simmering on the stove—or even hearing the term until recently—I find myself strangely moved by its endurance. It’s one thing for a recipe to be delicious; it’s another for it to have traveled a thousand years by way of human hands, human voices, and human hopes. There’s something grounding in that. Something steadying.

And though I didn’t grow up with wassail simmering on the stove—or even hearing the term until recently—I find myself strangely moved by its endurance. It’s one thing for a recipe to be delicious; it’s another for it to have traveled a thousand years by way of human hands, human voices, and human hopes. There’s something grounding in that. Something steadying.

The Christmas season has a way of piling up obligations faster than we can sort them. But wassail is simple. It asks nothing more of us than to pause. To warm a pot. To share. To lift a cup and offer the oldest winter wish we have: be well.

I also discovered that the traditional wassail song—yes, the one that starts “Here we come a-wassailing”—was originally a door-to-door verse of blessing, not a carol meant for polite living rooms. The lyrics have shifted over the centuries, but the spirit remains unchanged: we bring you good tidings, we knock on your door, we wish you health and cheer and perhaps a small something to sip before we head back out into the cold. Even Dickens knew the tradition well enough to tuck it into the edges of “A Christmas Carol,” describing bowls of steaming drink in festive windows as Scrooge walked through the city streets.

So here I am, a newcomer to this old custom, ladle in hand, following a trail that stretches from medieval halls to English orchards to mid-century American kitchens to my own stovetop. My son started this whole journey simply because he liked the sound of the word. And now, somehow, it’s become part of our Christmas season—a new tradition with ancient roots.

In the end, that’s what I love most about food history. You never know when a stray word or a forgotten recipe will open a door to the past. You never know which traditions will quietly ask to stay, even if they aren’t the ones you inherited. Wassail reminded me that sometimes we adopt a tradition not because it belongs to our past, but because it feels right in our present.

In the end, that’s what I love most about food history. You never know when a stray word or a forgotten recipe will open a door to the past. You never know which traditions will quietly ask to stay, even if they aren’t the ones you inherited. Wassail reminded me that sometimes we adopt a tradition not because it belongs to our past, but because it feels right in our present.

So here we come a-wassailing—not through snowy lanes or torch-lit orchards, but right here in the warm glow of the kitchen, with citrus peels curling in the pot and the scent of spices drifting through the house. The old blessing still holds:

Wes hál.

Be well.

Be warmed.

And may the coming year be generous to you in every way.