The American Diner

My first roadside diner experience came as a young man in my early twenties while on a road trip with a friend to visit their family in Mississippi. As we were passing through the state of Louisiana we came upon what looked like an oversized Airstream travel trailer parked on the side of the road. Its stainless steel exterior was trimmed in blue and white, with a solid blue awning over the door. On the roof was a large dark blue sign that read “Paradise Diner, Stop In” in bold white letters. And so we did.

Inside, along the windows were six or seven royal blue and white leatherette booths with Formica tables. Down the middle was a white Formica counter lined with several barstools sporting blue leatherette seats. And chrome was everywhere.

Behind the counter was a stainless steel wall with a large rectangle hole for passing food from the kitchen to the waitresses. On one side of the window was an array of coffee pots and on the other, a glass display containing slices of pies with swirls of toasted meringue piled at least four-inches high.

Behind the counter was a stainless steel wall with a large rectangle hole for passing food from the kitchen to the waitresses. On one side of the window was an array of coffee pots and on the other, a glass display containing slices of pies with swirls of toasted meringue piled at least four-inches high.

The menu was surprisingly modest, unlike modern diners of today where the menus resemble a short novel. This most likely, we surmised, was due to limited storage space in its small kitchen. My friend ordered a cheese burger with everything, extra pickles, and fries. I opted for the daily blue-plate special—meatloaf, mashed potatoes with brown gravy, and green beans. I still remember how impressed we were with the freshness and quantity of food on our plates. Both the mashed potatoes and the fries were the real deal, no frozen or dehydrated potatoes. And my green beans tasted like they were picked just that morning. Since then, I’ve made it a point to visit other roadside diners when the opportunity arises, as well as some stand alone units. And for the most part I’ve always been amazed at both the quantity, quality, and reasonable prices of their offerings.

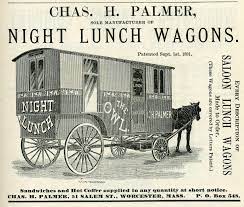

Most historians agree that the diners origin can be traced back to Walter Scott, a newspaper pressman at the Providence Journal who, in 1872, left the presses to sell late night coffee and sandwiches from a horse-drawn wagon parked outside the newspaper building. Soon, other enterprising young men began operating their own late night lunch wagons.

Coming out at dusk after most restaurants closed, these food wagons, know as “Nite Owls,” provided a cheap meal for evening-shift workers, theatergoers, and anyone else who was out late at night and hungry.

These first food wagons offered no tables, no chairs, and no protection from inclement weather. Customers had to eat their food while sitting on the curb or take it elsewhere to enjoy. But with the growing popularity of lunch wagons, so grew their evolution. In 1887 Samuel Jones redesigned his lunch wagon making it possible for customers to eat on a few stools inside. His new wagon was referred to as a “rolling restaurant.” And just as their design evolved so did their name. Folks began referring to them as “lunch cars,” then “dining cars,” and by 1924 simply “diners.

Some entrepreneurs discovered early on that building lunch cars was far more profitable than running them. One such businessman was T. H. Buckley of Worcester, Massachusetts who in 1887 constructed the first truly noteworthy lunch car he named “White House Cafe.” Soon Buckley’s lunch wagons became so popular that he was known as the “Lunch Wagon King.”

Some entrepreneurs discovered early on that building lunch cars was far more profitable than running them. One such businessman was T. H. Buckley of Worcester, Massachusetts who in 1887 constructed the first truly noteworthy lunch car he named “White House Cafe.” Soon Buckley’s lunch wagons became so popular that he was known as the “Lunch Wagon King.”

In 1898, Buckley renamed his company the T. H. Buckley Lunch Wagon Manufacturing and Catering Company. Not only did Buckley’s new company manufacture some of the finest lunch wagons of the times, they also dealt in cart supplies including dishes, knives, and decorative items. Buckley was also the first to add a cook stove to his lunch wagons.

Thomas Buckley died in 1903 at the age of 35, although his company continued producing lunch wagons until the mid 1900s. On May 14, 1961 the equipment, supplies, and all assets of T. H. Buckley Lunch Wagon and Catering company were liquidated at auction.

Three years after Buckley passed away two new entrepreneurs, Philip H. Duprey and Grenville Stoddard, became the next icons of the dining car industry. Founded in the city of the same name, Worcester Lunch Car and Carriage Company was the first to apply for and receive a patent on their diners. Their “Fancy Night Cafes” featured separate dining rooms, indoor bathrooms, a dining counter with fixed stools, and beautiful appointments. Unfortunately WLCC also succumbed to the times and shuttered is doors in 1957.

Three years after Buckley passed away two new entrepreneurs, Philip H. Duprey and Grenville Stoddard, became the next icons of the dining car industry. Founded in the city of the same name, Worcester Lunch Car and Carriage Company was the first to apply for and receive a patent on their diners. Their “Fancy Night Cafes” featured separate dining rooms, indoor bathrooms, a dining counter with fixed stools, and beautiful appointments. Unfortunately WLCC also succumbed to the times and shuttered is doors in 1957.

In the 1930s diners began to take on a streamlined futuristic look, with bullet-shaped exteriors and chrome and leatherette interiors, in an effort to upgrade their image. After World War II, diner builders continued to upgrade there units with Formica countertops, wood paneling, large windows, and terrazzo floors.

New Jersey became known as the diner capital of the world with some 600 diners, with New York running a close second. More than 350,000 Greek immigrates coming to the U.S., many settling in the New York/New Jersey area, brought their business and coffeehouse smarts which explains why so many diners in that area are Greek owned.

New Jersey became known as the diner capital of the world with some 600 diners, with New York running a close second. More than 350,000 Greek immigrates coming to the U.S., many settling in the New York/New Jersey area, brought their business and coffeehouse smarts which explains why so many diners in that area are Greek owned.

By the 1970s America’s interest in fabricated diners began to decline in favor of fast-food establishments. Many old diners responded by covering their stainless exteriors with brick or stone and adding mansard roofs. Some even added new additions to expand seating and production capacity. Diner manufacturers began closing their doors, and the three remaining companies began to fabricate new built-in-place diners.

Today, interest in the American diner has seen a revival of sorts. Many vintage diners have been given a new life by relocating to new sites in the U.S. as well as in Europe. Manufacturers of diner structures are experiencing orders for new units and remodeling projects in a retro style. The Massachusetts historical Commission has placed all vintage functioning diners in that state on the National Register of Historic Places, and nominations from other states continue to increase every year.

Today, interest in the American diner has seen a revival of sorts. Many vintage diners have been given a new life by relocating to new sites in the U.S. as well as in Europe. Manufacturers of diner structures are experiencing orders for new units and remodeling projects in a retro style. The Massachusetts historical Commission has placed all vintage functioning diners in that state on the National Register of Historic Places, and nominations from other states continue to increase every year.

Diners have been a part of the American landscape for over 100 years and their influence has touched our lives in many aspects including cooking, dining, design, culture and more.

Want to lean more about American diners? Pick up the book American Diner Then & Now written by Richard Gutman and published by Johns Hopkins University Press.