Take me out to the ball game . . .

When I was quite young, my father, an avid baseball enthusiast, was a driver for the local city bus line. In order to make extra money, during baseball season he would request to drive charters to the home games of our local baseball farm team, the Cats. One of the perks of being a charter driver was that he got free passes to watch the game. Many times he would take my mom and me with him. Other times mom would walk me to the bus stop and put me on his bus so he and I could have a father-son night out.

Even though I enjoyed the ball game and time with my father, the most exciting part of these evenings took place after the game. After we dropped the passengers off and returned to the “yard,” I got to accompany my dad inside the bus company building, affectionately referred to by the drivers as the “Club House.” It was there that my father reconciled his fares—transfer tickets, monies, logs, etc.—and turned them into the cashier. Afterwards he would take me downstairs where there were showers, lockers, and pool tables. I never tired of my visits to the Club House.

Needless to say, trips to the ball game always meant a special treat to snack on and a soda to wash it down. It was here that I was introduced to the delicious magic of Cracker Jacks. My dad would usually buy two boxes—one for me, one for himself—but of course, I got both prizes.

Needless to say, trips to the ball game always meant a special treat to snack on and a soda to wash it down. It was here that I was introduced to the delicious magic of Cracker Jacks. My dad would usually buy two boxes—one for me, one for himself—but of course, I got both prizes.

Cracker Jack has been around for some 120 years. If all of the Cracker Jack sold during that time were laid end-to-end they would circle the earth more than seventy-one times.

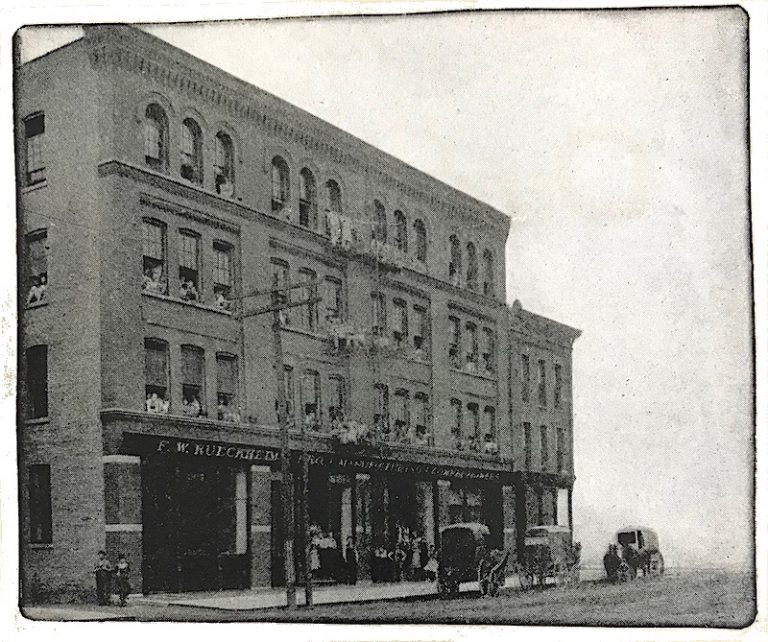

F. W. Rueckheim The story of Cracker Jack began when twenty-three-year-old Frederick William Rueckheim immigrated from Germany to America in 1869, seeking a new start in life after the Prussian-Austrian war. At first Frederick worked as a farmhand for his uncle who owned land in Washington Heights, a small town south of Chicago that was eventually integrated into the city. For this, he was paid $150 a year. But Frederick sought bigger things in life so after the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 he moved to the city to help with the removal of debris left by the tragic disaster.

Louis Rueckheim In the mid nineteenth century, popcorn had become a delicious and affordable American treat. And because the ingredients were plentiful and cheap, making and selling popcorn was a potentially good business opportunity. So in 1971 Frederick took his life savings of $200 and partnered with William Brinkmeyer (whose candy business was destroyed in the Chicago fire) to start a popcorn and confectionary company. They located their company on 113 Fourth Avenue in Chicago, where workers who were rebuilding the city provided them a readymade customer base. By the end of the next year Frederick bought out his partner and sent for his younger brother, Louis Rueckheim to join him in his venture. Together they formed F. W. Rueckheim & Brother with Frederick being responsible for strategy and marketing, while Louis’ was in overseeing manufacturing.

Louis Rueckheim In the mid nineteenth century, popcorn had become a delicious and affordable American treat. And because the ingredients were plentiful and cheap, making and selling popcorn was a potentially good business opportunity. So in 1971 Frederick took his life savings of $200 and partnered with William Brinkmeyer (whose candy business was destroyed in the Chicago fire) to start a popcorn and confectionary company. They located their company on 113 Fourth Avenue in Chicago, where workers who were rebuilding the city provided them a readymade customer base. By the end of the next year Frederick bought out his partner and sent for his younger brother, Louis Rueckheim to join him in his venture. Together they formed F. W. Rueckheim & Brother with Frederick being responsible for strategy and marketing, while Louis’ was in overseeing manufacturing.

The Rueckheim bothers business—producing popcorn bricks and other popcorn products— grew rapidly, requiring them to move the business five times over the next ten years. They finally settled down in a rented three-story brick structure on South Clinton street. But in 1887 the building, equipment and inventory were destroyed by fire. However within six months the brothers were able to regroup their business. This time they moved the factory into a new building on Deplanes Avenue with new equipment and a sprinkler system.

Although business was good, Fredrick and Louis wanted to expand their product line so the brothers began experimenting with a new confection that incorporated popcorn peanuts, and molasses. In 1893 their new product was introduced to the public at the World’s Columbia Exposition as “Candied Popcorn and Peanuts.” Unfortunately, although people loved the taste of the new product, they didn’t like how the stickiness of the molasses caused the product to clump together, making it messy and difficult to eat.

As a result of the Exposition feedback, Louis set out to solve the stickiness issue. In 1896 he successfully developed a formula that made the molasses coating dry and crisp—a formula that remains a closely guarded secret of the Cracker Jack Company, even today. In fact, since Louis Rueckheim developed his secret coating, the Cracker Jack formula has changed only one time. After Borden purchased the company in 1964, they exchanged white sugar for corn syrup.

It was also in 1896 when the Rueckheim brother’s popcorn, peanut, and molasses confection received and trademarked the name Cracker Jack. Legend has it that after a salesman (or production manager) tasted the creation, he exclaimed, “That’s a cracker jack!”—a slang term at the time that meant “something exceptional, splendid, or excellent. Thus the name was born. Later that spring F. W. Rueckheim & Brother began a national promotional campaign, manufacturing and shipping four and a half tons of Cracker Jack a day throughout the United States to backup the campaign.

It was also in 1896 when the Rueckheim brother’s popcorn, peanut, and molasses confection received and trademarked the name Cracker Jack. Legend has it that after a salesman (or production manager) tasted the creation, he exclaimed, “That’s a cracker jack!”—a slang term at the time that meant “something exceptional, splendid, or excellent. Thus the name was born. Later that spring F. W. Rueckheim & Brother began a national promotional campaign, manufacturing and shipping four and a half tons of Cracker Jack a day throughout the United States to backup the campaign.

For the first ten years Cracker Jack was sold from large tubs where store clerks scooped it into a bag or other container. Then in 1899 Henry Gottlieb Eckstein developed the “waxed sealed package” for the company, the moisture proof package still used today. That packaging allowed Cracker Jack to retain its freshness and be distributed worldwide in its own box. Eckstein’s contribution also resulted in him being made a partner in 1902, and the company name changed to Rueckheim Bros. & Eckstein.

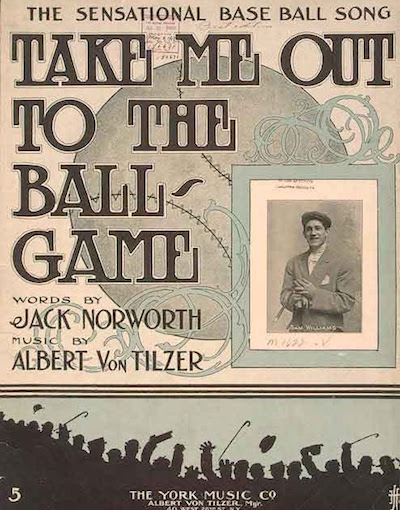

In 1908 songwriter Jack Norworth was on the New York subway when he spotted a sign that said “Ballgame Today at the Polo Grounds.” That sign began him thinking of baseball lyrics which he jotted down. When he arrived at work he immediately got with his friend Albert Von Tilzer who put the words to music. From this collaboration came the song containing the line that would come to immortalized Cracker Jack, “Buy me some peanuts and Cracker Jack.” And although Frederick was in charge of marketing, he had nothing to do with this, one of the most famous publicity campaigns in the Company’s history.

In 1908 songwriter Jack Norworth was on the New York subway when he spotted a sign that said “Ballgame Today at the Polo Grounds.” That sign began him thinking of baseball lyrics which he jotted down. When he arrived at work he immediately got with his friend Albert Von Tilzer who put the words to music. From this collaboration came the song containing the line that would come to immortalized Cracker Jack, “Buy me some peanuts and Cracker Jack.” And although Frederick was in charge of marketing, he had nothing to do with this, one of the most famous publicity campaigns in the Company’s history.

First performed at the Ziegfeld Follies by Norworth’s wife, soprano Nora Bayes, the song quickly became a standard at every major league baseball park in America, and one of the country’s most widely sung songs, providing Cracker Jack years of free publicty. It is interesting to note that at that time neither Norworth or Tilzer had ever been to a baseball game. It would be 32 and 20 years later respectively before the two songwriters would see their first game.

Another major marketing idea, including prizes in each box of Cracker Jack, was also one that Frederick Rueckheim may have “borrowed” from a rival, the Checkers candy company. While some say that the practice actually started around the turn of the century, the phrase “A prize in every box” was added to the Cracker Jack label in 1912, according to company history.

The first Cracker Jack prizes were paper, and included items like dolls, games, and pictures of movie stars and baseball players. There were also metal prizes produced by the Tootsietoys Company of Chicago. These toys included thimbles, irons, animal figures and tops. Then there were the coupons printed on all Cracker Jack labels that could be redeemed for a wide array of toys, jewelry, books, table linens, and sporting goods. And regardless of what the prizes were, they had to appeal to both boys and girls alike.

The iconic characters, Sailor Jack and his dog Bingo, that appear on all Cracker Jack packaging were first introduced in 1916 in print advertisements. In 1918, it was decided to add Sailor Jack and his dog to the box, a decision that turned out so popular that they still appear on all Cracker Jack packaging, even today.

In 1922, the company changed its name to The Cracker Jack Company.

In 1922, the company changed its name to The Cracker Jack Company.

One of the most successful Cracker Jack marketing campaigns of all times took place from May of 1933 to May 1936. The Cracker Jack Mystery Club offered membership by collecting and mailing the company 10 Presidential Coins (later 3, then 5), which could be found inside boxes of the molasses coated popcorn and peanut treat with question marks on the label. The Cracker Jack company would stamp the back of your coins with “cancelled” and return them with a membership certificate and small gift. There was a total of thirty-one coins (Grover Cleveland’s two non-consecutive terms were stamped on the same coin) beginning with George Washington and ending with Franklin D. Roosevelt. More than 200,000 children join the Mystery Club during those three years.

The Cracker Jack company was purchased by Borden in 1964 after a bidding war with

Frito-Lay. Then in 1997, Borden sold the brand to PepsiCo, who quickly incorporated it into their Frito-Lay portfolio and production was moved to the Wyandot Snacks plant in Marion, Ohio.

On April 30, 2013, in an effort to reinvigorate waining sales, Frito-Lay announced a slight reformulation of the original Cracker Jack by adding more peanuts and updating prizes to be more relevant to today's consumer. They also announced expanding the product line with the addition of a new popcorn product called Cracker Jack’D. Distinct form the original, Cracker Jack’D comes in a number of flavors, including Power Bites a caffeine laced product. Packing for the new line is also distinct, using all black rather than the traditional red and white label and featuring a close-up version of Sailor Jack and Bingo. Cracker Jack’d does not include prizes in its packages.

On April 30, 2013, in an effort to reinvigorate waining sales, Frito-Lay announced a slight reformulation of the original Cracker Jack by adding more peanuts and updating prizes to be more relevant to today's consumer. They also announced expanding the product line with the addition of a new popcorn product called Cracker Jack’D. Distinct form the original, Cracker Jack’D comes in a number of flavors, including Power Bites a caffeine laced product. Packing for the new line is also distinct, using all black rather than the traditional red and white label and featuring a close-up version of Sailor Jack and Bingo. Cracker Jack’d does not include prizes in its packages.

There you have it, the story of Cracker Jack. So next time you go to a ballgame, why not enjoy it with a box or two of the sport's favorite candied popcorn and peanut snacks. And be sure to keep the prizes for yourself