Pokeweed, America’s forgotten vegetable

For much of my early childhood our weekly evening meals, though plentiful, were generally vegetarian based. Beef, pork, and poultry were reserved for weekends or special occasions, and fish was simply not a favored protein in our house. One of my father’s favorite suppers was momma’s slow-cooked pinto beans, a pan of hot country cornbread (baked until the top was a crisp mahogany color), and collard or mustard greens cooked in some of the bacon grease from an old Crisco can she kept next to the stove.

It seemed that just about every time my momma served this meal, we were obliged to listen to my father tell how he missed his aunt Alta’s (with whom he lived after his father died of gangrene) poke salad. How after he finished his chores, she would send him to gather a big sack of these greens from the fence rows and ditches along the country roads where it grew wild. When he returned, she would begin the laborious task of preparing them for their supper.

It seemed that just about every time my momma served this meal, we were obliged to listen to my father tell how he missed his aunt Alta’s (with whom he lived after his father died of gangrene) poke salad. How after he finished his chores, she would send him to gather a big sack of these greens from the fence rows and ditches along the country roads where it grew wild. When he returned, she would begin the laborious task of preparing them for their supper.

Now for the life of me, my young mind just couldn’t wrap around the idea of why anyone would want to cook their salad, much less enjoy it as much as my father alleged. It was years later that I discovered my father was referring to pokeweed, a wild toxic green that grows throughout much of the United States, but is especially prevalent in Appalachia, the Midwest, and the American South. It was not salad at all, but instead a type of greens that when properly prepared tasted similar to mustard greens. And its name, although somewhat of a misnomer, is actually pronounced poke “sallet,” a French word meaning salad. It seems the name poke “salad” was popularized by the 1969 country song Polk Salad Annie, by Tony Joe White. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z-MD8SPW6Eo)

American pokeweed is a flowering herbaceous perennial plant belonging to the Phytolaccaceae family. Because pokeweed is poisonous to livestock and domestic animals, many of today’s farmers consider it an invasive pest and want it destroyed. And while the leaves and stalks of this species are a nutritional powerhouse, high in vitamin A, C, iron, and calcium, its high toxicity will make humans extremely ill (perhaps even fatal) if not properly cooked.

The pokeweed plant can grow eight to ten feet in height with sturdy purplish stalks and small white flowers that grow in clusters, turning into shiny red to dark purple, almost black, berries as the plant matures. These berries are a good food source for a number of songbirds, including the mockingbird, cardinal, and thrasher. It’s bright green leaves have the appearance of salad greens, which may partially be why some people erroneously refer to it as “salad.”

The pokeweed plant can grow eight to ten feet in height with sturdy purplish stalks and small white flowers that grow in clusters, turning into shiny red to dark purple, almost black, berries as the plant matures. These berries are a good food source for a number of songbirds, including the mockingbird, cardinal, and thrasher. It’s bright green leaves have the appearance of salad greens, which may partially be why some people erroneously refer to it as “salad.”

Pokeweed should be picked when the plant is young and tender, ideally no more than one to two feet in height, and before the stalks show any signs of purple. The leaves and stems should be thoroughly washed, then parboiled at least three times, draining, squeezing them out, and changing the water after each boil. They can then be sautéed with some onion, bacon fat, salt and pepper before serving. Poke, like spinach and other greens cook down considerably, so it takes starting with quite a large bunch to make a meal.

It’s purported that even before the arrival of Europeans, the indigenous peoples of eastern North America were using the pokeweed plant for a number of purposes, including medicinal. The dried and crushed root was used as a poultice to treat everything from hemorrhoids to tumor and other skin conditions. A tea made from the berries was used to treat rheumatism, arthritis, and dysentery. The leaves were used as a poultice for treating acne, scabs, and to stop bleeding.

In fact, even today the plant’s antiviral properties are thought to have the potential for treating cancer, herpes, HIV, and leukemia. Research on the plant’s potential medicinal uses are ongoing.

In fact, even today the plant’s antiviral properties are thought to have the potential for treating cancer, herpes, HIV, and leukemia. Research on the plant’s potential medicinal uses are ongoing.

And while reported that the Cherokee crushed together pokeweed berries and grapes to make a sweetened drink, ingesting the plants berries, and especially the roots is not recommended under any circumstances. Doing so may cause severe illness and even death, particularly in young children and the elderly.

A number of American Indian tribes were known to use pokeweed in their religious and witchcraft practices. Many tribesmen thought wearing beads made from the plants berries would ward off evil spirits and infectious diseases.

Indigenous tribes also used pokeweed to make dyes used for coloring clothing, marking their weapons and horses, and even their own skin. Mature leaves were used to make yellow dye, the berry juice to make reds, purples, and pinks.

Perhaps one of the most popular uses of pokeweed berries was to make ink. Crushing the ripe berries, straining out the seeds, and fermenting the juice produces a brownish ink that resists fading. In fact, it is reported that the American  Constitution was written with pokeweed berry ink on hemp paper — still legible today.

Constitution was written with pokeweed berry ink on hemp paper — still legible today.

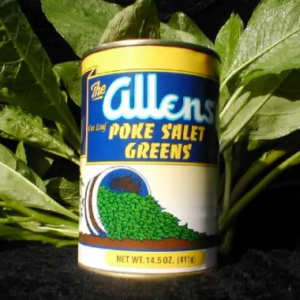

At one time, despite its toxic attributes, this “poverty food” became so popular that it was commercially canned by both the Bush Brothers cannery in Tennessee and Allen Canning Company in Siloam Springs, Arkansas and sold in grocers throughout the South. Allens was the last company to produce the greens, discontinuing them in April of 2000, due primarily to the lack of people interested in supplying them with poke.

For those of you interested in learning more about this forgotten vegetable, tasting a plate of them, or just looking for a couple days of fun, there are two, yes two, annual poke sallet festivals you can attend. One is the 70th Annual Harlan County Poke Sallet Festival in Harlan, Kentucky, taking place this year from June 5th through June 7th. The other is the 47th Annual Poke Sallet Festival in Whitleyville, Jackson County, Tennessee, May 8th and 9th.

For those of you interested in learning more about this forgotten vegetable, tasting a plate of them, or just looking for a couple days of fun, there are two, yes two, annual poke sallet festivals you can attend. One is the 70th Annual Harlan County Poke Sallet Festival in Harlan, Kentucky, taking place this year from June 5th through June 7th. The other is the 47th Annual Poke Sallet Festival in Whitleyville, Jackson County, Tennessee, May 8th and 9th.