Canning, How It Started and Where It’s Come

Growing up in my household, one was certainly well acquainted with canned foods. While descended from a line of Southeastern Oklahoma dirt farmers we certainly enjoyed our share of home-canned foods—seasonal vegetables, fruits, pickles, and jams. But as the years went by and farm life gave way to city living, we became more and more dependent on commercially canned foods. By the time I finished high school store bought canned foods were about the only kind my family used.

Today there’s not a grocer or supermarket in the country without isles and isles of tinned vegetables, fruits, meats, soups, and sauces. Additionally, you’ll find jars and bottles of pickles, jams, and condiments of every kind. In fact, were it not for canned foods, meals for as many as 60% of Americans would be adversely impacted because of the high cost and lack of availability of fresh foods.

How it all begin.

Archeologists have discovered evidence that suggests even in prehistoric times man has sought ways of preserving foods for long periods of time. One of the first methods was salting and drying, a technique still used today. Later they discovered some foods, such as jams and other confiture could be preserved using oils and vinegars. But the 18th century brought about methods that in time totally change the way we preserve foods.

Shortly before the Napoleonic Wars, the French government offered a cash award of 12,000 francs to anyone who could develop a cheap, effective way of preserving rations for its Grande Armée.

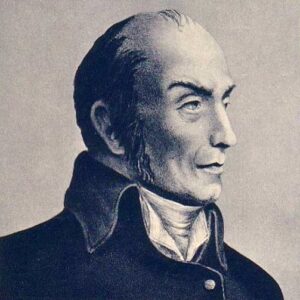

In 1795, Nicolas Appert, confectioner, brewer, and chef at the Palais Royal Hotel in Chalons, France, after hearing of the governments offer, took on the challenge and began a 14-year quest to win the prize. And since chemistry was a little know science at the time, Appert’s preservation experiments were very much a process of trial and error. Although he had no knowledge of why the process worked, Appert discovered that by placing foodstuffs in glass jars, sealing them with cork and wax, and placing them in boiling water for an extended period, the contents did not spoil. Beginning with soups, vegetables, juices, jams, jellies, and syrups, he eventually expanded to meats, fowl, dairy, and even fully prepared meals.

In 1795, Nicolas Appert, confectioner, brewer, and chef at the Palais Royal Hotel in Chalons, France, after hearing of the governments offer, took on the challenge and began a 14-year quest to win the prize. And since chemistry was a little know science at the time, Appert’s preservation experiments were very much a process of trial and error. Although he had no knowledge of why the process worked, Appert discovered that by placing foodstuffs in glass jars, sealing them with cork and wax, and placing them in boiling water for an extended period, the contents did not spoil. Beginning with soups, vegetables, juices, jams, jellies, and syrups, he eventually expanded to meats, fowl, dairy, and even fully prepared meals.

In 1810, Appert, after publishing his findings in The Art of Preserving All Kinds of Animal and Vegetable Substances for Several Years, was awarded the 12,000 franc prize by Count Montelivert, French minister of the interior. However, it would be another fifty years before fellow Frenchman, Louis Pasteur, would discover the reason for the foods lack of spoilage, and developed the process of pasteurization.

From Jars to Cans

Although Appert’s method of preventing food spoilage was very effective, his glass jars were an inherent problem due to breakage.  Response to the issue came from another countryman, Philippe de Girard, who developed a process similar to Appert’s method but used tin-coated, hand-soldered sheet steel cans instead of glass jars. In 1810, the same year Appert received his award, Girard’s agent, British merchant Peter Durand, applied for and received a patent for the idea. However, neither Girard nor Durand were interested in pursuing food canning and instead sold the patent to two other Englishman, Bryan Donkin and John Hall, in 1812.

Response to the issue came from another countryman, Philippe de Girard, who developed a process similar to Appert’s method but used tin-coated, hand-soldered sheet steel cans instead of glass jars. In 1810, the same year Appert received his award, Girard’s agent, British merchant Peter Durand, applied for and received a patent for the idea. However, neither Girard nor Durand were interested in pursuing food canning and instead sold the patent to two other Englishman, Bryan Donkin and John Hall, in 1812.

Donkin and Hall refined the Durand patent and established the world’s first commercial cannery in London on Southwark Park Road, and by 1813 had secured a contract for 150 pounds of tinned canned beef from the Royal Navy. It seems British sailors liked the canned beef so much that the following year Britain’s Admiralty ordered another 2,939 pounds, and by 1821 that number increased almost fourfold. Soon Donkin-Hall tin cans were being used to preserve not only food but everything from turpentine to gun powder as well.

Canning Comes to America

Robert Ayers introduced America to canning in 1812, the same year that Donkin and Hall started their cannery. His small factory, located in New York City used improved tin-plated iron cans to preserve oysters, meats, fruits, and vegetables. However the process was still a crude, time-consuming process.

In 1802, Thomas Kensett immigrated to America from England where he had apprenticed in London as an engraver. After several failed business ventures, Kensett, in his early 30s, began experimenting with canning. What piqued Kensett’s interest in food preservation remains a mystery, but by 1822 he and his father-in-law Ezra formed the partnership of Daggett & Kensett, located near the New York City docks. Their canning business experimented with preserving meats, gravies, vegetables, and other food in cans made from thin tinplate. By January 1825 they had obtained a patent on their revolutionary process.

In 1802, Thomas Kensett immigrated to America from England where he had apprenticed in London as an engraver. After several failed business ventures, Kensett, in his early 30s, began experimenting with canning. What piqued Kensett’s interest in food preservation remains a mystery, but by 1822 he and his father-in-law Ezra formed the partnership of Daggett & Kensett, located near the New York City docks. Their canning business experimented with preserving meats, gravies, vegetables, and other food in cans made from thin tinplate. By January 1825 they had obtained a patent on their revolutionary process.

As numerous wars throughout the world created a large, ever increasing demand for canned foods in order to feed the armies and navies, a number of small canning manufacturers, ignoring existing patents, opened to take advantage of the huge demand.

But the commercial success of canned foods in America didn’t come about until Gail Borden’s 1856 invention — condensed milk. You see, the lack of good refrigeration made maintaining fresh milk in growing urban areas both difficult and expensive. Borden’s condensed milk addressed the issue. The American Civil War created even more demand for canned food and milk.

In 1901, the American Can Company was founded, at the time producing 90% of the tin cans in the United States.

All this demand for canned food was not without its problems, including how to open them. Those early cans of tin laminated steel or iron had to be opened with hammer and chisel, knives, or even shooting them with a gun. It was not until 1860, almost 50 years later, that thanks to the thinner walled cans Ezra J. Warner invented America’s first can opener.

Canning on the home front

It was several years after commercial canning started that home canning began to take hold. At first home canners used a process much like Appert’s method, in that foodstuffs were put into jars, stoppered with corks, sealed with wax, and boiled to preserve the contents, a technique that was cumbersome and anything but foolproof.

It was several years after commercial canning started that home canning began to take hold. At first home canners used a process much like Appert’s method, in that foodstuffs were put into jars, stoppered with corks, sealed with wax, and boiled to preserve the contents, a technique that was cumbersome and anything but foolproof.

Enter New Jersey born John Landis Mason who in 1858, invented and patented the first glass jar with a screw-on lid. Mason’s square-shouldered jar, with its threaded neck on which a threaded metal cap screwed down over a rubber seal to create an airtight seal, became an integral part of home canning for the next 100 years.

Enter New Jersey born John Landis Mason who in 1858, invented and patented the first glass jar with a screw-on lid. Mason’s square-shouldered jar, with its threaded neck on which a threaded metal cap screwed down over a rubber seal to create an airtight seal, became an integral part of home canning for the next 100 years.

Unfortunately, Mason failed to patent one crucial part of his invention—the rubber ring on the underside of the flat metal part of the lid—for another 10 years. During this time, a number of other glass manufacturers began successfully making mason jars eventually pushing Mason out of business. Mason died penniless in 1902.

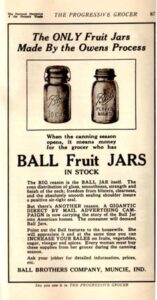

In 1880, about a year after Mason’s original patent expired, five brothers—Frank, Edmund, George, William, and Lucius Ball—started a company in Buffalo, New York producing tin cans and glass jars. They eventually moved their operation, Ball Brothers Manufacturing Company, to Muncie, Indiana, where they concentrated on making glass jars using Mason’s original design. Soon they were the largest producers of mason jars in America.

In 1880, about a year after Mason’s original patent expired, five brothers—Frank, Edmund, George, William, and Lucius Ball—started a company in Buffalo, New York producing tin cans and glass jars. They eventually moved their operation, Ball Brothers Manufacturing Company, to Muncie, Indiana, where they concentrated on making glass jars using Mason’s original design. Soon they were the largest producers of mason jars in America.

The next generation of canning jars came about in 1903 when Alexander Kerr and John Giles started the Hermatic Closure Company making metal lids and spring clips. The next year, Kerr changed the company name to Kerr Glass Manufacturing Company and began making “Economy” jars. Instead of screw-on lids, Kerr’s jars used a clamp-type lid with a rubber gasket attached to the underside of the lid, a design patented by Julius Landsberger.

The next generation of canning jars came about in 1903 when Alexander Kerr and John Giles started the Hermatic Closure Company making metal lids and spring clips. The next year, Kerr changed the company name to Kerr Glass Manufacturing Company and began making “Economy” jars. Instead of screw-on lids, Kerr’s jars used a clamp-type lid with a rubber gasket attached to the underside of the lid, a design patented by Julius Landsberger.

In 1915, Kerr devised another simple one-piece flat disc and gasket lid held in place by a screw-on ring band. He called his lids “self-sealing, because once processed you no longer needed the ring band. These are the same lids used today.

Kerr is also responsible for introducing the 3-linch wide-mouth mason jar. Soon afterwards, Ball copied Kerr’s design and started producing wide-mouth jars as well.

The availability of mason jars in the late 19th century brought about a boom in home canning. The first cookbook dedicated to canning, Canning and Preserving by food writer Sarah Tyson Rorer was published in 1887.

The home canning sensation was so strong that it even had an architectural influence. Free-standing “summer kitchens” began springing up as a means to keeping the main home kitchen cool during the weeks-long canning season.

Home canning reached a peak during World War II when Americans were encouraged to help the war effort by growing “victory gardens” in order to preserve extra food. There were even “propaganda posters” urging housewives to “Can All You Can.” But in the late 40s, with the war ending and improved commercial canning and freezing technology, home canning slid into a decline.

Home canning reached a peak during World War II when Americans were encouraged to help the war effort by growing “victory gardens” in order to preserve extra food. There were even “propaganda posters” urging housewives to “Can All You Can.” But in the late 40s, with the war ending and improved commercial canning and freezing technology, home canning slid into a decline.

Throughout the years interest in home canning, like the mythical phoenix, rises and falls, the latest upswing being during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Modern technological advances continue to improve canned foods, making them safer, longer-lasting, and more nutritious than ever before. There are even canned products with standards of such high quality as to be considered gourmet. With today’s extensive lines of canned foods, almost any Americans can enjoy a delicious meal anywhere and at anytime, at a price they can afford.