Icons of Summer: Kool-Aid and Popsicles

While my childhood was one of humble existence, we were not without some of the middle-class niceties of the times, thanks to a an extremely hard working father and a mother with the uncanny ability to stretch a dollar further than anyone I've ever known.

Growing up, I loved just about everything that summer had to offer--fishing, baseball, camping, swimming, and get-togathers with friends and family. One of my favorite summertime pleasures was hearing the jingly notes of "Turkey in the Straw" cutting through the hot afternoon air. The ice cream truck was on its way. Occasionally my mom would slip me a nickel so I could join the pack of young thrashing arms to buy my favorite red Popsicle. I can still remember sitting on the front porch trying to suck down all of that icy, sweet popsicle goodness before it melted.

Popsicle

As the somewhat dubious story goes, one chilly evening in 1905 in the San Francisco Bay city of Oakland, 11-year-old Frank Epperson made himself a cup of powdered soda mix (it's unclear where he got powdered soda, as I can find no evidence of its existence in 1905) and water and left it on his porch overnight. Temperatures dropped severely during the night and the next morning young Epperson found his concoction completely frozen with the wooden stirrer sticking out. Sampling his icy potion, Epperson realized he had accidently discovered a new delicacy and declared his frozen pop-on-a-stick the "Epsicle."

While it is said that Epperson realized on that morning in 1905 that he had been blessed with a winning idea, it would be 18 years later before he decided to test market the frozen treat beyond friends in his own neighborhood. In the summer of 1923, Frank took daily batches of his Epsicle to Neptune Beach, an amusement part in nearby Alamada, where he sold all he could make.

Bolstered by this success, the next year Frank decided to patent his "frozen drink on a stick" and expand his fledgling business to a larger market area. By this time, Epperson had children of his own who always referred to the frozen treat as "pop's sicle." So at their urging, Frank filed and received his patent in the name of Popsicle instead of Epsicle.

In 1925 Epperson took on the Joe Lowe Company of New York as his business partner and together they began distributing Popsicle across the country. Unfortunately by the end of the decade Frank had fallen on hard times and was forced to sell them his rights to the brand. Epperson later said, "I was flat and had to liquidate all my assets," adding, " I haven't been the same since." Epperson died in 1983 and is buried in Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland.

August 29th is National Cherry (America's Favorite Flavor) Popsicle Day.

As it turned out, the Lowe Company's superior marketing genius allowed Popsicle to quickly become a nationwide success. For example, during the height of the depression the company began producing a two-stick version, making it possible for two people to share one Popsicle for just a nickel. Rumor has it that this single move created sales of 8,000 units at New York's Coney Island in only one day.

In 1989 the Lowe Company sold the Popsicle brand to Unilever who combined it with their already successful Good Humor brand and quickly expanded the lineup beyond its original seven fruity flavors. Today, Unilever sells more than two billion Popsicles a year in a wide array of flavors, ranging from grape and strawberry to mango and avocado, although cherry has always been the most popular. In 1986 the two-stick version was discontinued at the request of moms throughout America, declaring it too messy and difficult to eat.

I rarely ever eat popsicles any more, although my reasons why are not really clear, even to me. Perhaps it's because one must rush through eating ice pops for fear of them melting and messing up one's clothes. Perhaps it's because they took away the iconic two sticks, making them no different than other ice pops. Or perhaps adulthood has simply taken away the thrill and excitement that once overcame me every time I heard the jingly sound of the ice cream truck slowly making its way through the neighborhood.

Kool-Aid

Another of my favorite summertime treats was enjoying an ice-cold "jelly glass" (how many of you remember jelly glasses?) of Kool-Aid. For just five cents a package, plus a cup of sugar, and some tap water, we were able to make two quarts of delicious fruit-flavored beverage--affordable even on my parents' stringent budget. It seems there was always a pitcher of Kool-Aid goodness in our refrigerator. My favorite flavors were orange and strawberry, but since my father preferred the more grown-up taste of lemon-lime and pink lemonade, that's what was usually available.

More than 563 million gallons of KOOL-AID are consumed each year, with more than 225 million gallons in the summer.

Edwin Elijah Perkins was born in Lewis, Iowa on January 8, 1889 to store owners David and Kizandra (Kizzie) Perkins. Four years after Edwin's birth, the Perkinses sold their store in Lewis and moved to a farm some ten miles from Beaver City in Furnas County, Nebraska. There the family lived for seven years in a three-room sod house, surviving extreme heat, droughts, and pestilence through long hours of hard work in the fields, raising livestock, pigs, and chickens.

Then in January of 1900, David Perkins traded the farm for a general store in the small village of Hendley, so young Edwin and his eight brothers and sisters could go to better schools. In the afternoons after school, Edwin began helping his father clerk in the store. One day a family friend, upon returning from shopping in Hastings, brought his father some packages of a new dessert--Jell-O. Edwin was so enthralled with Jell-O that he persuaded his father to carry it in their store.

Bitten by the entrepreneurial bug early on, Edwin responded to a magazine advertisement on how to become a manufacturer. Soon he received the requested information, along with formulas and labels that read "Manufactured by Perkins Products Co." It wasn't long before he was in his mother's kitchen experimenting with medicines, flavorings and other concoctions. By the time Edwin graduated from high school he had developed a line of products which were successfully sold door-to-door, through mail order, and eventually independent agents.

During these early years, Perkins, in his continuing quest to become successful, also bought a small hand printing press on which he printed his own labels and promotional materials, as well as small jobs for other businesses and neighbors. He even published a weekly newspaper he called the Hendley Delphic. And if his Perkins product line, a printing business, and newspaper publishing were not enough, Edwin also became the Hendley postmaster.

successful, also bought a small hand printing press on which he printed his own labels and promotional materials, as well as small jobs for other businesses and neighbors. He even published a weekly newspaper he called the Hendley Delphic. And if his Perkins product line, a printing business, and newspaper publishing were not enough, Edwin also became the Hendley postmaster.

In September, 1918, Edwin Perkins married his childhood sweetheart Kathryn Shoemaker, the daughter of Hendley's only doctor. Edwin and "Kitty," as Kathryn preferred to be called, were totally devoted to each other in every facet of their lives, including Edwin's business dealings.

Then in February of 1920, Edwin and Kitty moved eighty miles east to Hastings, where advanced highways and multiple railroads provided a better distribution point for their business. By August of that same year Edwin's parents also moved to Hastings, where they helped in the couple's growing business. Over the next two years Perkins Products Co., a true family business employing the entire Perkins family with the exception of sister Faye, moved twice more to accommodate its continued growth.

One of the most popular items in the Perkins lineup was a summertime soft drink called "Fruit-Smack." Available in six flavors, a four-ounce bottle was so concentrated that a family could make a pitcher full of fruity drink for only a few cents. But Fruit-Smack wasn't without problems--heavy glass bottles, breakage, and leaky corks. Edwin knew he had to find a solution.

Perkins, remembering his much admired Jell-O, felt that the solution to Fruit-Smack's problems was to similarly turn it into a dry, concentrated powder, packaged in an envelope, that the consumer could easily rehydrate later. Edwin was also convinced that if he was successful in making Fruit-Smack the easy-to-ship, easy-to-use product he envisioned, it would attract national food brokers and allow him to get out of the mail order business. So by 1927 Perkins and his chemists had developed Kool-Aid's six initial flavors--raspberry, cherry, grape, orange, root beer, and strawberry.

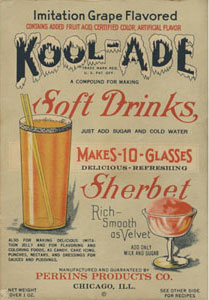

In his search for a catchy name and sticking to his penchant for hyphenated words (Onor-Maid, Nix-O-Time, Motor-Vigor, Glos-Comb, and Jel-Aid), he came up with the product's original name, "Kool-Ade," which was trademarked in 1928. There were however problems with the use of the word "Ade." Some say government regulators contended that it could only be used with fruit juice products. Others say he was threatened with a lawsuit by another party if he continued to use the original name. For whatever the reason, in 1934 Perkins trademarked a new spelling for his powdered beverage--"Kool-Aid."

Other major setbacks encountered in the development of Kool-Aid included packaging that would keep the product dry and fresh without coming apart, convincing both local and national food brokers to distribute it, and of course, growth capital. But Edwin's tenacity, salesmanship, and marketing genius allowed him to overcome all obstacles, and Kool-Aid quickly became a true success.

By 1931, two years after the Great Depression began, demand for Kool-Aid continued to grow. So much in fact that the Perkins Products location in Hastings was bursting at its seams, making a search for new quarters a necessity. So Edwin and his sales manager and new partner Fred Schmitt relocated the Kool-Aid business to a 13,000-square-foot plant in Chicago. Business continued to be strong and three years later the company added 20,000-square-feet to the factory, followed by another expansion in 1939 that doubled capacity.

In June of 1949 the plant moved once more to a 135,000-square-foot facility, plus they added a night shift. The following year Perkins employed 300 factory workers (80% women), 50 office personnel, produced 323 million packets of Kool-Aid, and enjoyed sales of more than 10 million dollars.

On February 16, 1953 Edwin Perkins announced that he had sold Perkins Products to General Foods, who coincidently also owned the Jell-O brand. At the age of 64, after more than 50 years in business, Perkins retired. He and his wife Kitty set up philanthropic foundations and divided their time between homes in Chicago and Miami Beach, where their daughter Nancy lived.

Edwin E. Perkins died in 1961, following a long illness. Kitty Perkins followed sixteen years later. Both are buried in Parkview Cemetery in Hastings, Nebraska.

Kool-Aid drinkers are no longer restricted to just single envelopes of powder mix to which sugar is added to make 2 quarts of beverage. Today, Kool-Aid is available in various sized canisters with sugar included, concentrated sugar-free Kool-Aid liquid that will produce twenty-four 8-ounce glasses of the stuff, and more. Ironically, even Kool-Aid soft drinks have returned. But regardless which Kool-Aid product you choose, two-quarts will definitely cost you more than a nickel--or even the original price of ten-cents.

As for me, it's probably been at least thirty-five years since I last purchased a package of Kool-Aid. During my sons upbringing, their mother insisted they drink water, tea, or fruit juice, rather than sugary beverages like soda and Kool-Aid. Now that she and I are empty nesters, we keep bottled water, cans of flavored seltzer, and the occasional beer in our frig--no fuss, no muss. But sometimes when I see a Kool-Aid display, or watch a TV commercial, my mind takes me back to the times when on a hot, sultry Texas day, I could hardly wait to suck down an icy cold jelly glass of sweet delicious Kool-Aid.