Cake Mix: Redefining Baking in America

Growing up in the mid-twentieth century, I observed first-hand a number of food innovations and convenience products that directly affected how the American housewife prepared the family meal. Arguably, the one product that brought about the biggest change was the invention of boxed cake mixes.

I can remember when every pie and cake my mom baked was made from scratch. Then came the fifties and, like other American households, convenience items became commonplace in our home, as well. It seems my mom fell in love with Betty and Duncan, eventually even turning to canned frostings. From those days forward, only after much begging would she make one of her popular scratch cakes, and I'm honestly not sure she didn't do a little cheating even then.

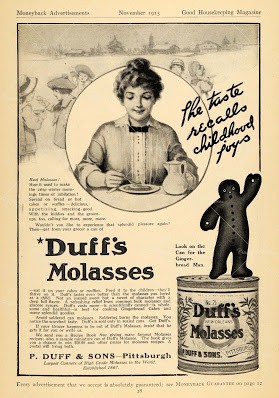

Boxed cake mixes in America actually got their start in the early 1930s when P. Duff and Sons, a Pittsburg molasses canning company, found itself with a surplus of molasses.  Its founder John D. Duff, who had successfully found a way to dehydrate his excess syrup, began searching for a way to utilize his molasses powder. Employing techniques used by the Pearl Milling Company to launch Aunt Jemima's "just add water" pancake mix, Duff developed a gingerbread cake mix.

Its founder John D. Duff, who had successfully found a way to dehydrate his excess syrup, began searching for a way to utilize his molasses powder. Employing techniques used by the Pearl Milling Company to launch Aunt Jemima's "just add water" pancake mix, Duff developed a gingerbread cake mix.

Later that year, Duff applied for a U.S. patent for his new invention. In his application, Duff explained that for housewives to go to the expense and inconvenience of maintaining the ingredients needed to bake cake for their family was no longer necessary when they could purchase a can of Duff and Sons gingerbread cake mix for 21 cents a 14-ounce can. Yes, cake mixes were first marketed in cans.

"When I got to France I realized I didn't know very much about food at all. I'd had those cakes from cake mixes or the ones that have a lot of baking powder in them. A really food French cake doesn't have anything like that in it - it's all egg power." - Julia Child

By the end of 1933 Duff's baking mix, now available in other flavors including devil's food and spice, was granted its first patent--no. 1,931,892. However, in an effort to improve its mixes the company had already began tweaking its formula. John became aware that the taste of his cake mix was a bit off due to the use of powdered eggs, so his new formula required housewives to add fresh eggs. Not only did this change resolve the  off-taste issue but actually improved the rise and texture of the finished product. On June 13, 1933, Duff filed for his second patent, writing in his application, "The housewife and the purchasing public in general seem to prefer fresh eggs and hence the use of dried or powdered egg is somewhat of a handicap from a psychological standpoint." On October 8, 1935, patent no. 2,016,320 was granted.

off-taste issue but actually improved the rise and texture of the finished product. On June 13, 1933, Duff filed for his second patent, writing in his application, "The housewife and the purchasing public in general seem to prefer fresh eggs and hence the use of dried or powdered egg is somewhat of a handicap from a psychological standpoint." On October 8, 1935, patent no. 2,016,320 was granted.

Probably the most well known myth about cake mix development is that Ernest Dichter, psychologist and the man who coined the phrase "focus group," was working with General Mills on how to improve cake mix sales. As the story goes, Dichter determined that housewives wanted more involvement in the baking process, so from then on Betty Crocker cake mixes required adding fresh eggs. While Dichter did work with General Mills, he did so in the 1950s, some fifteen years after Duff was granted his patent for eggless cake mix. A later survey determined that although homemakers said they preferred to add their own eggs, they really liked the convenience of those mixes that include eggs.

By the end of World War II and the late 1940s there were more than 200 brands of cake mix, including labels like Swans Down, Dromedary, X-Pert, Helen's, Joy, Occident, and PY-O-My. Of course, the largest share of the market was held by the big flour companies who had spent the war years getting ready to jump into the cake mix game once our troops were home. Taking a lesson from J. Duff and Sons, flour mills decided they had to do more than just sell flour--convenience was now the name of the game.

"My idea of baking is buying a ready-made cake mix and throwing in an egg." - Cilla Black

It is interesting that while as previously mentioned American housewives really liked cake mix that included eggs, only Pillsbury stayed with the add water only mix, while GM's Betty Crocker and Consolidated Mills' Duncan Hines (later sold to Procter & Gamble) went the add-your-own-fresh-eggs route.

Between 1956 and 1960 cake mix sales began to flatten (increasing only 5% during that time) and many companies shut their doors. The remaining cake mix companies began searching for what went wrong and what was needed to kick-start sales. Enter marketing psychologist Ernest Dichter, who proclaimed the problem to be frosting, not eggs. Since baking the cake was so simple, the housewife wanted to make the baked goods their own through cake decorating and other creativeness. Soon photographs on cake mix boxes and in magazines began to showcase elaborate cake constructions and over the top icing techniques. It is interesting that a product developed to save time has since become a culinary time-filler.

Today, boxed cake mixes are a staple in every supermarket, household pantry, and yes, many commercial bakeries in the United States, as well as most developed countries in the world. And with American home bakers using more than 60 million cake mixes a year, the homemade scratch cake is quite an endangered species.

Make It: Homemade Cake Mix